Most religions and moral systems see one of the great human problems as selfishness. A common and unifying philosophy is that personal development is a transcendence from the self to a larger purpose.

Around the middle of last century, Abraham Maslow, Carl Rogers and others aimed to liberate and enlarge the self. This was the beginning of the self-esteem movement and humanistic psychology, and it is so embedded in Western thinking now that it is almost second nature.

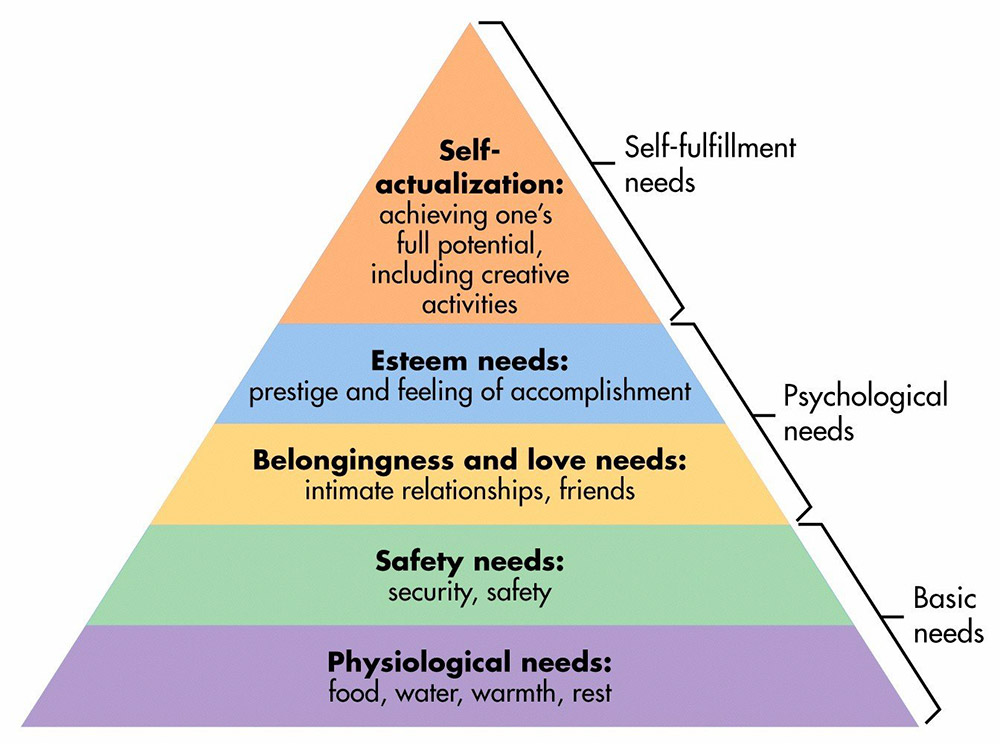

Taught in universities and applied to everything from marketing to relationship counselling, the most famous model of this era is Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

In this model, we start out trying to satisfy our physical needs, move through belonging and love, and finally end up at the pinnacle of development, which is our esteem and self-actualisation needs, experiencing autonomy and living in a way that expresses our authentic self.

MASLOW’S VIEW OF RELATIONSHIPS

A Maslow model of relationships has them supporting the individual self-actualisation of each of the partners. In “A Psychology of Difference: The American Lectures” (1996), Otto Rank wrote:

Simply speaking, this is the definition of a relationship: one individual is helping the other to develop and grow, without infringing too much on the other’s personality.

So, partners in a relationship coach each other as each seeks to realise their most authentic self, and we should choose a partner who will help us elicit the best version of ourselves.

This is very often the view that we have of power exchange dynamics such as D/s and M/s, and you will see it threaded through many of our discussions about how BDSM relationships work. It’s the common view that the Dominant in some way takes “responsibility” for the growth of their submissive, or that the submissive’s role is to nurture and support the Dominant in their psychological and self-fulfilment needs.

The common refrain is that power exchange relationships are, at their core, relationships. So, of course partners support each other in their growth.

Supporting each other in growing is not really the key flaw in looking at relationships through a Maslow lens. What many people find is that it is an unsatisfying version of self-fulfilment.

Firstly, relationships tend to work in the opposite way. If you go into a relationship seeking self-actualisation, you will find that relationships tend to drag you away from the goals of self. More often, the self melds into a single unit, and your identity changes. It becomes less about giving and receiving, altruism and selfishness, because when you give to the unit you give to a piece of yourself.

And secondly, people tend to experience their deepest sense of meaning not when they have placidly met their other needs, but when they come together to meet some kind of shared goal.

IS THERE A BETTER WAY OF LOOKING AT RELATIONSHIPS?

If we rewind back quite a long way, Aristotle proposed his own hierarchy — The Four Kinds of Happiness.

In this model, the lowest kind of happiness is material pleasures, like nice food and clothing, and a fancy house and car. The next level is achievement — our own earned and recognised success. Above that is generativity — the happiness we get from giving back to others. And at the pinnacle is moral joy, which is the glowing satisfaction we get when we have surrendered ourselves to some noble cause or unconditional love.

While Maslow’s hierarchy moves from the collective to the relational to the individual, Aristotle moves from the individual to the relational, and finally to transcending the self with the collective.

So, in the Four Happiness model, you might go into a relationship in a fit of passion, but hopefully the relationship is successful and the joy becomes about other things — curling up side-by-side in the evening to share a favourite TV show, kissing your toddler on the head as you tuck him in, feeling gratitude in having the family gathered around the table for a birthday or Thanksgiving.

The self has melded into the relationship. And, even more than that, as that matures it becomes about something larger. Whether that’s family, friends or wider community.

This is a move away from the me-generation, towards covenant, fusion and surrendering love. I think we can see a model of power exchange dynamic in Aristotle just as much as we can see it in Maslow, but while Maslow’s could easily turn into self-absorption, Aristotle offers us ideals that we may never fully achieve but can, perhaps, aspire to.